Photographers Without Borders spoke with five storytellers about conservation,

the environment and why it's vital to shine a light on conservation stories. Each gave

their experience and thoughts on what's happening on our planet and what

we need to do to protect the ecosystems we all share.

David Coulson

David Coulson is a conservation photojournalist whose work focuses on examining the complex, fraught and indivisible relationships between people and planet. He has covered endangered turtles in Ontario, followed the migration of porcupine caribou in Alaska and journeyed to the disappearing jungles of Indonesia where orangutans are dramatically in decline. Believing that the camera can be a tool for understanding and awareness, David aims to reveal our profound connections to the earth and the urgent need to protect it.

What is conservation photography to you?

For me, conservation photography is proactive and issue-oriented. It's photography used as a tool for change. In wildlife or landscape photography, that's often going out and taking a really nice photo. But for conservation photographers, there's a bit more thinking behind what the photos are going to do. What's the purpose behind them? Rather than just going out and photographing something, I'm looking for a collaborator or a partner to put the photos to use. I want my images to be put to work and have no qualms calling myself an advocate.

What experience impacted you as a conservation photographer?

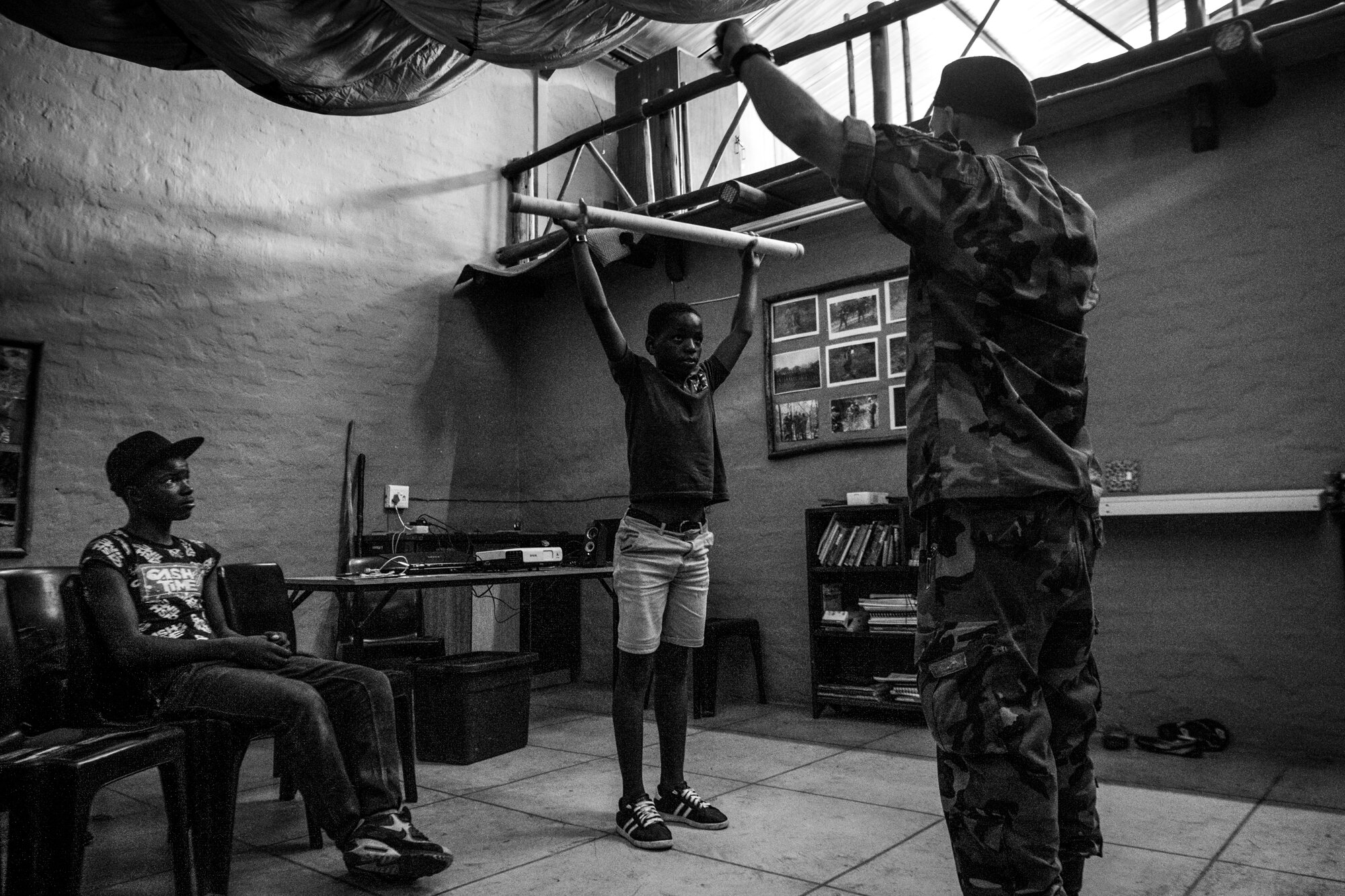

I went to South Africa to film the documentary “Beyond the Gun,” and that experience led to a shift in my perspective on conservation. A lot of conservation, for example, focuses on endangered species. In this case, it would be the rhino. We worked with an organization called Nourish that tackles the issue of poaching from the lens of poverty, rather than the lens of people.

Coming from an environmental studies background, I had focused on conservation through the lens of just the species. But South Africa opened my eyes to a more holistic lens of what conservation is about and how important the intersection of social issues, like poverty, apartheid and discrimination, play into conservation. There's not a lot of emphasis on the broader societal issues that play into conservation. For me, those are the kinds of stories I want to tell.

What role do ethics play in your storytelling?

Ethics play a part in how stories are told. When it comes to wildlife, you respect the wildlife in how you take your photos. You don't disturb them or their habitat in any major way.

When it involves people, I think of how to get beyond this photographer-subject dichotomy where you're telling someone's story. You can try to show or share and remove a lot of power dynamics that are inherent in photography, especially when you're in places as an outsider.

I think intention and intent are important as a conservation photographer. You have to consider the impact. How can I use these photos as tools for change? Think about the integrity of the story. What's the best way to tell this story? You often deal with very complicated stories, and you have to make sure you're not just relying on your own assumptions for what a story might be. Make sure to do your research and ask the experts to fill in any gaps.

Justin Mott

Justin Mott is an award-winning photographer based in Vietnam and has worked for the New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian, The Washington Post, TIME, Greenpeace, and The Guardian, among others. An avid animal welfare advocate, he pivoted the focus of his work in 2018 to wildlife photojournalism and conservation photography. He's currently working on his long-term global personal project titled "Kindred Guardians." https://www.justinmott.com/

What is conservation photography to you?

Conservation photography is creating long-form stories that have an impact to get people to think and see the human side. I'd love for people to care about animals. But for people who don't care about animals, I want them to at least see the human side of things as well. Maybe they can bond there and it will have an impact on them.

For me, it's not just getting stories out in international publications. I live in Vietnam, and I've covered Southeast Asia for a long time, My stories tend to end up in European and American magazines. But my goal now is to get my stories out to people where I live and people who are a part of the problem. Vietnam is one of the largest consumers of rhino horns, so I want to educate people who are part of this chain through my stories.

Why are you passionate about being a conservation photographer?

Rhinos are being killed off to extinction. So I started my personal project with the Northern White Rhinos to shed light on this problem and show how there were only two left. But I also covered the rhino horn trading in Vietnam by photographing people consuming the horn, documenting the dealers and pretending to be a buyer.

It was weird to photograph the story of a severed rhino horn and then, 10 years later, to meet the two last Northern White Rhinos. I had such mixed feelings. There are a lot of stories of animal cruelty—bear bile farms and pangolin consumption—but they always made me so angry and sad. I tried to stay away from those types of assignments because they would mess with me emotionally. But a few years back, I realized that I got into photography to do stories that I care about and are meaningful to me. That's how I got back to stories that make a difference and hopefully can have an impact.

What is one of your most memorable photos or series, and why?

The theme of my project "Kindred Guardians" is to capture the bond between humans and animals and turn them into separate stories. I have all these different chapters that are their own story, but they feed into this larger story.

I can spend weeks on each story, which is nice. For example, with my story about sloths, I had gone to Suriname to photograph a lady that takes care of sloths. After about three days, I started to notice how she's constantly looking up into the trees for sloths, even when she's driving. I love those little details that you can get when you have more time. And I can weave that into the story. I want to bring people in by having them care about the lady, and then maybe they'll understand what's happening with deforestation.

The whole idea of my project is to show people who take care of animals and the connection that results. Hopefully, that leads people to learn a little bit more about the situation and to a bigger, broader understanding of what's happening in conservation.

Natasha Hirt

Natasha Hirt is a conservation photographer based in Tkaronto with a passion for documenting and communicating environmental science through her art. She has taken this passion across Canada, documenting conservation stories with non-profit, Indigenous and government organizations. Natasha aims to use her photography to influence positive environmental change, and to connect people with the land and each other. Follow her on Instagram @natsha.hirt

What is conservation photography to you?

Conservation photography is a tool to bridge art and science to make science accessible to non-scientists. It's clear language and visuals people can relate to and understand with the scientific jargon. Conservation photography is more than just taking visually pleasing pictures. It needs to have an educational element for the audience to be able to take something away, whether that's a descriptive Instagram caption or a call to action for a specific project.

What impact do you hope your work has?

One of the installation photography projects that I did a couple of years ago, I brought a whole bunch of garbage that I had collected from people's houses on garbage day, like chairs and TVs. I installed it and photographed it in the Rouge National Urban Park in Toronto. Those images were printed on large-scale vinyl and installed in the park for about a month. That project specifically talked about how humans use so much, and it had a lot of impact on me. I tried to go Zero Waste after that.

What role do ethics play in your storytelling?

In wildlife photography, in particular, people can get crazy with unethical practices, like baiting, getting too close and disturbing sensitive ecosystems to get the perfect photograph. But as a conservation photographer, you have to consider how your actions are impacting the subject matter that you're working with. If I'm in a wetland, I can't disturb the entire wetland to get a photo of a bird. You have to be respectful of the space that you're in, as well as the subject matter that you're photographing. In my own conservation photography, I've become increasingly aware of how important it is to include Indigenous knowledge and voices in the conversation.

What's one of your most memorable photos or photo series, and why?

I documented nesting turtles while working out of Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site. I was driving to work on a rainy spring morning and three or four snapping turtles—which are federally recognized as a species at risk—came out of the river and crossed the road.

They began digging their nests in the soft gravelly soil on the side of the road. I pulled over and communicated with the turtle researchers. While I waited for them to arrive, I had the most wonderful experience photographing these beautiful creatures while they were digging their nests and laying their eggs. I was also there in the fall, so I got to document some hatchling snapping turtles. It's magical that that happened.

Clare Stone

Clare Stone is based in Ottawa, Ontario and has a background in Environmental Studies and Ecosystem Management. Stone is actively involved in the conservation community, and her latest inspiration has been eliminating cigarette litter and plastic pollution as a team member in A Greener Future's Butt Blitz. Follow her stories on Instagram @domraylove.

Why are you passionate about being a conservation photographer?

I took Environmental Studies at Algonquin College and the Ecosystem Management Technician Program at Fleming. Conservation photography is a combination of my passions and interests, and I'm still exploring what it means. Being a conservation photographer is a way to share my voice and show others what I see, value and care about. The story of who I am is represented in the photos I take.

I feel conservation photography creates social and environmental change when it comes to environmental awareness, but it also has a social aspect to it by connecting a viewer to a specific issue.

What impact do you hope your work has?

I am extremely passionate about environmental issues. I recently did a project on plastic nurdles—tiny, lentil-sized plastic pieces that are used to make plastics and can be detrimental to our ecosystems. They can be easily mistaken as food and ingested by birds, turtles and other types of wildlife. I spotted them on the local beaches in Ottawa where I live, and I knew that I had to do something about it.

Due to the pandemic, it wasn't possible to have a lot of in-person activities. So I challenged myself to create images and stories with photography and post on Instagram. I asked myself, how can I show people nurdles and just how small they are? How do I show that microplastics are present in freshwater ecosystems and are not just an ocean issue? Because of those photos, I've had in-depth conversations with people about possible solutions and plastic-free alternatives. In a recent post, I challenge people to do l a five-minute beach cleanup and a few people are going to take on that challenge. I hope my work continues to inspire and get people thinking about the environment.

What role do ethics play in your storytelling?

I'm highlighting environmental issues and focussing on wildlife in my work, so I try to incorporate ethical storytelling into what I'm doing. Recently, there was a barn owl in my area, and I didn't want to stress it out by getting too close to it. I watched it as it followed the sounds of something moving underneath the snow.

But then I thought, am I preventing it from hunting? How long can I sit here and not disturb it? So I took a few photos from a good distance and then went on my way. I try my best to put myself in their shoes, paws, hooves or talons. And I consider what message I'm sending when I post the photo. I want to make it clear that I'm not super close—I'm using a telephoto lens and am not chasing the owl.

What are you most concerned about right now?

I'm always volunteering. And I started highlighting what I was doing on social media with my photos and posts and encouraging others to get involved as well. Currently, I'm volunteering with an environmental organization called A Greener Future in a Butt Blitz - so there are different teams all over Canada and we're collecting cigarette butts that have been discarded. We're collecting them to raise awareness about the environmental impacts of cigarette waste but also sending them to Terra Cycle which actually has a recycling program for them. It really inspired me to create a photo series with my collected butts - trying to share the message about what you can do with litter. I collected 741 butts in over 3 days.

Sharon Guynup

Sharon Guynup is a journalist, author, photographer and video producer who covers science, wildlife conservation and environmental issues. She focuses on wildlife trafficking, conservation initiatives and zoonotic disease. Her work has appeared in National Geographic and The New York Times, and she is currently a Global Fellow with the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and the Global Risk and Resilience Program. http://www.sharonguyn.com

What is conservation storytelling?

I think our goal in conservation storytelling is if we're going to save wildlife and ecosystems, we need to tell the whole story. It's the people who live beside wildlife. It's the threats that they face. It's the conservation efforts to save them. Every conservation issue at this point is extremely complex because there are many intertwining threats. It requires not only creative solutions, but it requires broad storytelling to outline what the issues are today.

It's important to tell stories and flesh out characters, whether it's about the conservationists working to save animals, the biologists in the field, the people who have to share a landscape with a species or the animals themselves.

We need to go back to the very basic human desire to hear stories. I try to remember that in my work by telling the big stories because I feel the media landscape has changed so dramatically. Reporters, staff writers and staff photographers are very focused. They have to bang out a lot of work on very intense deadlines. That means much of what we read lacks the big picture and the context, which is a lot of the power behind the issue.

Why are you passionate about telling conservation stories?

I've always been attuned to animals. I not only love the beauty of life on the planet, but over the years, I've become acutely aware of the interconnectedness of life on Earth. Pulling threads from the web of life makes the whole web collapse. We're becoming acutely aware of the consequences of human activities.

Back in 2005, I spent six months doing research, going to conferences and interviewing many of the same experts that are being interviewed about COVID-19. Back then, the researchers raised the red flag to say travel and trade bring deforestation, bring livestock into wild areas, bring hunting and the wildlife trade. All of these things present very serious disease risks. And new infectious diseases are emerging at an ever-increasing rate. We need to rethink our use of nature in terms of our own health now that we're more than a year into a global pandemic.

What impact has your work had?

Six years ago, I looked into a place called the Tiger Temple—a Buddhist monastery in Thailand that doubled as a tiger tourism venue. My team and I proved they were trading tigers into the illegal Asian black market. The day after the story was published with National Geographic, the Bangkok Post picked it up. The largest TV news station in Thailand ran a seven-minute segment from the multimedia piece that we ran with the story. Then, news outlets across the globe picked it up.

Our story was a spark, and nonprofits, biologists, conservationists and Thai citizens buried the Environment Minister's office with letters and email protests. Within four months, officials confiscated the rest of the tigers and shut the Tiger Temple down. There had been 178 Tigers there.

What are you most concerned about right now?

Climate change has completely altered the threat level to the planet. The clock is ticking. But I don't want to end there. Nature is resilient, and with accurate scientific information, political will and investment, there's a lot that can be saved. I think it's important for people to realize that by saving large landscapes where many species live, we're also protecting the water we drink, the air we breathe and ourselves. It's important for us as storytellers to remind people that we are part of life on this planet. Our existence and future well-being is woven into the well-being of the planet. The more we can show examples of that message and remind people of this web of life that we are part of, the better chance we have of saving remaining habitats and endangered species and preventing future pandemics.